Recently I had a teaching experience at a school where I have taught for the past 12 years, including as a head teacher and interim director. This experience that I was teaching was a multi-sensory approach to Havdalah. I brought several different kinds of Besamim, a sweet-smelling mixture of Cinnamon, Cloves, Star of Anise, Cardamom, & Persian Lime. One of my procurements was a bottle of essence of elderflower that the kids thought smelled sweet from afar and gross up close. I also brought an orange that I had covered with cloves and aromatic branches and cut flowers, a Sephardi and Mizrahi minhag, or custom, to symbolize the sweetness of Shabbat that we want to take with us into the following week.

0 Comments

Parshat VaYeshev Drash by Martin Rawlings-Fein Shabbat Shalom and and early Happy Chanukah to all of you! Tonight we get the first draft of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, a story with a definite star. In VaYeshev, or where [Jacob] “Settled,” we meet Joseph, favorite child of Jacob, grandchild of Isaac, great-grandchild of Abraham, who, by all accounts, is the leading person of zis own story -- and by the way, I'll be using “z” pronouns for Joseph’s gender -- you'll see why later. Joseph is gifted an ornamental coat by zis father, or a coat of many colors as many of us know the story. Joseph then finds zis brothers out in the field and tells them about dreams that zie had wherein zis brothers gathered bundles of grain, and those bundles bowed to Joseph’s. In another, the sun, the moon, and eleven stars also bowed to Joseph, which angers the brothers so much that they sell Joseph into slavery. Joseph’s siblings bring the coat back soaked in blood to say that a wild animal has eaten zim, much to the dismay of their father, Jacob. Then we get to know Joseph in another setting as zie becomes a personal servant to Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh's guard. Joseph grows and becomes zis own person, only to be thrown into prison after a false accusation of rape. The Parsha begins with a portrait of Jacob and his children. Joseph has 11 male siblings, and all of them are envious of Joseph. Zie brings terrible reports of the siblings to zis father. Joseph also takes pleasure in telling the siblings of zis dreams. As one commentator Avivah Zornberg writes in her book Genesis: The Beginning of Desire, “Joseph behaves with the narcissism of youth, with a dangerous unawareness of the inner worlds of others.” Let’s face it, Joseph is a bit of a gossip, running to father all the time with a story or two about zis brothers. However, in all of this, the last straw is one that zie cannot control, a father’s love. Joseph’s father, Jacob, loved zim so much that he gave Joseph an ornamented tunic. Joseph’s brothers were already upset with zim. Still, when they saw this tangible gift that ultimately symbolized Jacob's celebrated love for Joseph, their feelings developed into nothing but seething hatred. The ketonet passim, or ornamented tunic, was probably the fanciest bit of clothing anyone had ever seen. Midrashim, such as B’reishit Rabbah 84:7, describes Joseph as “penciling [zis] eyes, curling [zis] hair, and lifting [zis] heel,” in essence dressing in the fiercest drag, and by gifting zim with the ornamented coat, Jacob shows his acceptance/approval of his child as zie is. This idea of Joseph, the drag queen, is an old one. From the early centuries of the common era, rabbis discussed how different Joseph was and the feminine aspects of zis demeanor. Why would any of zis shepherding brothers want an ornamented tunic like that? Perhaps there was more than envy behind their gaze, and maybe the gift highlighted Joseph's feminine side or gender nonconformity. They began plotting the end of their sibling not long after the fiercest gift was given. Homo/biphobia and transphobia are all sides of the same coin, misogyny. Joseph’s gender nonconformity is written in the text as part of zis physical description, which mirrors prior texts about women, using language about zis form and beauty that the Torah does not usually use for men. Now I won’t lie to you. The idea that Joseph was one of us, a gender outlaw, a drag queen, and queer as funk, is a breath of fresh air for me. Here I thought I would be discussing sinat hinam or baseless hatred that I didn’t know well, but in fact, I know this kind of hate all too well. I live through it. As a trans person, I navigate the world where people disrespect my gender daily. You know it is serious when a man like myself gets called she or told that I could never be a man by folks who don’t know me. What if Joseph were the most fabulous queen, even 1700 years before the common era, and we never got to know just how fantastic all because some scribes refused to see Joseph in all zis queerness, the same way that people today refuse to see trans folks in all our beauty. But I digress. We do get to know the person that Joseph was, whether in drag or out. That person grew into a space where zie could be zieself fully and learn to interpret zis and others’ dreams. How amazing is that? That one could be so introspective and be so close to another that their dreams are like open books. I couldn’t do it, but then I am not Joseph, and I don’t have the fiercest frock. As LGBTQ people, in 2022, we are still disowned by our own families. Sometimes we can recover part of our families of origin after years of work on all sides. Sometimes like Joseph, we have to choose to make a family with people far away from our origins. I gave up on many of my family who couldn’t get my pronouns right or struggled with my name. My mother gave me hope and never gave up celebrating me in all my masculinity. When I was a child, we shopped in the boy’s section of department stores, and I dressed the way I wanted, and I was comfortable because she saw me. My mother saw my true self before I ever did. As a father, I see Jacob getting that tunic back covered in blood, and all I can think is don’t give up hope. It is hard to lose a child, yet every day, parents willingly let their children leave when they come out. The struggle is how do we reach the folks who can’t wrap their head around difference and allow for those breakthrough conversations to happen? In this Parshah, we see Joseph grow and change from the selfish youth who does not see the inner machinations that would cause anyone to hate and transition into a person who can interpret the dreams of others by divining their internal struggle. It is truly a spectacular journey that trans folks go through with families of origin intact and not. And we don’t have to accept trivial tolerance. Joseph’s brothers tolerated him until they didn’t. Tolerance is never enough. We should take nothing less than a full celebration of the unique beings that we are without reservation. Jacob, Joseph’s father, knew this. He celebrated his child’s uniqueness with aplomb and gifted zim with that ornamental tunic that made it to Broadway. May all of our stories end up there! Keyn y'hi ratzon May It Be So.  Parashat Shemini No Sacrifice Needed: Modern Day Nadav and Avihu by Martin Rawlings-Fein on Saturday April 18, 2009 24 Nissan, 5769 Leviticus 9:1 - 11:47 In Parashat Shemini the Mishkan (tabernacle) is dedicated, Aaron is installed as high priest, and Aaron’s sons Nadav and Avihu suffer an unfortunate fiery death. The “strange,” “alien,” or “unauthorized” fire Aaron’s sons brought to the altar was an act blasphemous enough to cause G-d to lash out at the young men in anger, killing them instantly. I struggle with the similarities between this condemning, angry G-d and some of the members of my own family. Turning the Torah until it speaks to me as a father, son, and a transsexual bisexual man, I try to find answers in the text. Sometimes though, the answers I find provide no easy solution to the problem, and no matter what I try, that angry patriarchal tyrant still looks more like my uncle than G-d. As a father I am haunted by the knowledge that the G-d I pray to in my 21st century life would end a human life in flames. Perhaps context will provide some clue to G-d’s abhorrent behavior. When the Israelites’ were slaves, for generations they had to follow Egyptian religious practices, including praying to idols and burning incense on altars. Were Nadav and Avihu just following what they had been doing since they were young or were they irreverently drunk (as some commentators suggest)? Both of these back stories fail to justify G-d’s extreme reaction. G-d smote Nadav and Avihu because s/he didn’t like their method of approach? Their fire was somehow not good enough? I still can’t stomach this violent G-d. How do we, as modern day Jews, reconcile the fact that G-d burned the sons of Aaron alive? As a parent who could never think of my child dying in that way, I struggle with G-d, the text, and the feeling that there are no easy answers. In August of 2008 when the “No on 8 Campaign” was in full swing, a family member called to wish me a happy birthday. As we were shooting the breeze he said that he really wanted to have a serious conversation with me. I was bracing myself for the question about the $30 I owed him from his daughter’s school fundraiser. What happened next was unnerving. He said that he wanted me to move out of San Francisco because he was certain that G-d was going to smite the city. I thanked him for his concern and asked him why he thought this was going to happen – that I wasn’t surprised by this new development says a lot about our relationship. I engage him in theological debates all the time, this was no different. Yet, it was, because the answer was very difficult to hear. His reasoning was that G-d was disappointed in those who had abandoned the covenant and that the cities had become wicked places where homosexuals and people with loose morals had congregated. He was concerned that these sinners were reinterpreting G-d’s word and blaspheming against him. As he spoke, I realized that the blasphemers he was talking about were me and my chosen family. To him, we were all Nadav and Avihu bringing strange fire to G-d and therefore retribution was waiting in the wings. He was trying to get me to leave San Francisco but his words were tearing at my soul. I found a way to disengage from the conversation and began trembling after the call. I tried to laugh it off with my mother during her phone call later in the day; apparently he had called other family members and given them the same warning. I am, however, the only family member who would fit the description of the sinner that he thought G-d would take the time to smite. When I first transitioned from female-to-male my family of origin smote me with their words and actions. They stopped inviting me to family events, took my pictures down off the walls, and created an expectation that my soul would not be “saved” if I continued my wicked ways. One family member went so far as to write me a letter stating that she loved me with all her heart but hated the man I had become because G-d had sanctioned her to hate the things he saw as abominable. My reaction was pretty swift; I created pockets of community and family from those whom did truly love and care for me. I didn’t look back to my family of origin except to those who did not abandon me. Now that I am grown and have a daughter of my own, we all see things in a new light. The family of origin that rejected me because of my method of approach to life has finally grown enough in their own spiritual space to see me as the man I am. I tend to see G-d, like my family of origin, as an ever changing force. We as Jews are often commanded to remember and to never forget what has happened. This grounds us in the past but does not negate our progressive yearnings. Through this lens I can look back at the slaying of Nadav and Avihu and see how G-d has transitioned with us through the struggle of who we are as a people. Similarly, my family of origin can now call me on my birthday and plead with me to leave a city that they see as wicked. Because in addition to seeing my sexual preference, my gender identity and my religious choices, they also see me as a father, a son, and a man that they care about. Those they label wicked and abominable are, like me, just struggling to be seen as human beings rather than blasphemers’ bringing strange fire to G-d. When those who only see the literal translation learn the deeper lessons of the text, then we will all truly be closer to G-d with no sacrifice needed.  Making Mensches: A Periodic Table Making Mensches: A Periodic Table Today is the 17th of Nisan and the 2nd day of the Omer. For those scratching your heads about the "Omer." The Omer is a unit of counting barley sheaves that marks each of the forty-nine days of traveling the desert from Egypt to Sinai, which culminates with the celebration of Shavuot. Shavuot is when the Jews celebrate giving of the Torah, and we are all there, present, past, and future, becoming a nation committed to serving G!d. We have many holidays this time of year, not just Passover. But back to the Omer, why do we count bundles of barley to remember our time in the desert? Well, think of the countdown as a way to show our Antici...passion for the Torah to come. We countdown for rockets headed to the heavens, for ball drops in Times Square, and for all types of events. Even the Swedish rock band Europe can't escape their 1986 hit, "The Final Countdown," which continues playing everywhere there is a countdown. When we start the count, it begins on the second day of Passover, and some people will stop getting haircuts as this time is also a period of semi-mourning. The story goes that a plague killed 1200 pairs of Rabbi Akiva's students (Babylonian Talmud Yebamoth 62b). Still, the epidemic might mean they died in revolt because the Bar Kokhba Rebellion was active around the same time. Some Jewish customs forbid haircuts, shaving, and listening to instrumental music, unlike vocals, so the Maccabeats are a-okay, or conducting weddings, parties, and dinners with dancing. The thirty-third day of the Counting of the Omer, or Lag BaOmer, is when these restrictions end for Ashkenazim, and many Jewish folks will get their hair cut or have their young child's first haircut on Lag BaOmer. Sephardim tend to have their customs around that, as do Mizrachi Jews. Some carry on with their semi-mourning until Shavuot. It all depends on the individual community, its standards, and minhag. We count these barley sheaves because the Jewish calendar is predominantly agricultural. During Passover, there is a shift from praying for rain to praying for dew. Out of this agricultural calendar that moves with the moon, we get another innovation, the Middot—or working on one's good characteristics through reflection and bettering one aspect for each day for the 49 days. From agrarian to spiritual in just 49 steps, over 2000 years as the first known Middot compiled by Rabbi Hillel in the 1st century BCE (or Before the Common Era)1. I find these innovations over time exciting and awesome and try counting each day with intention like generations before. If you want to try to say the blessing tonight, please follow below: When we "count the Omer," we recite a blessing each night to count the next day: The count uses days ("Today is the twenty-fifth day of the Omer,") and weeks and days once there are weeks to count ("which is three weeks and five days of the Omer.”) Start Here:

End with this:

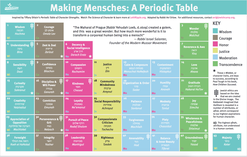

Have fun checking out the resources below like the Velveteen Rabbi, Ritual Well and a periodic table of Middot for exploring Middot with children. Resources: Omer - Velveteen Rabbi - Blogs.com Middot Omer Calendar -- Jewish Ritual - Ritualwell Making Mensches: A Periodic Table (A favorite of mine for exploring Middot with kids.) References: 1. The letters CE or BCE in conjunction with a year mean after or before year 1. https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/ce-bce-what-do-they-mean.html  Our table runner for Passover with Pharaoh (Joker) on the horse and Moses (Steve) and Miriam (Alex) leading the Israelites to the other side of the Sea of Reeds. Our table runner for Passover with Pharaoh (Joker) on the horse and Moses (Steve) and Miriam (Alex) leading the Israelites to the other side of the Sea of Reeds. Tonight begins Passover, or Pesach, the time of the year when as Jews, some get super serious about kashering the kitchen and eschew all things leavened. Pesach is a major Jewish holiday that celebrates the Israelites' exodus from slavery in Egypt. The holiday occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nisan, or the month of April this year. This year, it coincides with Ramadan, this month, and Easter, which is Sunday for those who don't know. This new blog is about being on the path or "On the Derech." You may or may not be familiar with the term "Off the Derech," most often used negatively and is applied to a broad range of ex-Orthodox Jewish individuals. While I wasn't born into an Orthodox family, it was my first entrance into Judaism as a youth. After discovering my father's Jewish heritage, I searched for a path, found Orthodox communities, and fell in love with Torah, Talmud, and study in general. I soon had Orthodox friends and teachers in the community. One minor issue: I was trans, bi, and living a closeted stealth life after high school. Over 20 years ago, when I finally came out as both bi and trans, it altered my relationship with Judaism. I wasn't "Off the Derech," but I was on my self-made path. I explored many of the Jewish movements offered and found my way to my and others' mish-mash of different pathways called "Reformadox." Torah teaches us that we went forth from Egypt, or Mitzrayim, as a "mixed multitude," or erev rav. I like the idea of all the people having their own paths, just like us. It is part of life and how we maneuver kashrut, mitzvot, Halakhah, secularism, Torah, and tradition. "On the Derech" is my home for spreading my thoughts about how we are all searching for our path. Welcome to my blog about it all! And Chag Sameach to everyone! Martin Parashat Shemot

Saving Our Youth from the Crocodiles by Martin Rawlings-Fein on Friday January 08, 2010 Tevet 22 5770 Exodus 1:1 - 6:1 Shemot, or Names, is this weeks Parashat and in it we follow the life of Moses through birth, exile, and his eventual return to Egypt. We begin by reading the names of those sons of Israel who have followed Joseph down to Egypt and then we turn left and end up with a Pharaoh who just happens to either not know, or care, that Joseph ever existed. As the reading goes on we find that this new Pharaoh says to his people, “Behold, the people of the children of Israel are more numerous and stronger than we are. Get ready, let us deal shrewdly with them, lest they increase, and a war befall us, and they join our enemies and depart from the land”. (Exodus 1:9- 10) He starts off slow with a tax to build grain houses but the Hebrews happily give and continue their stay in Egypt. “So the Egyptians enslaved the children of Israel with back breaking labor”. (Exodus 1:13) And when they continued to multiply even under such a heavy burden, the gloves came off in a way that chills. And he [the Pharaoh] said, [to the Midwives] “When you deliver the Hebrew women, and you see on the birthstool, if it is a son, you shall put him to death, but if it is a daughter, she may live”. (Exodus 1:16) We are told the names of the Midwives, but Torah never reveals the name of the Pharaoh. The Egyptian ruler is a vehicle to drive the story rather than an individual of note. Moses’ parents bear him under this oppressive regime, and his mother hides him for three months until she can safely take him to the Nile marshes and send his sister to watch over him. The baby is plucked from the Nile by the Pharoah’s daughter. She names him Moses and he goes on to lead the Israelite people out of Egypt. Moses’ new mother is a G-d send to the little child in the reeds. Upon seeing the distress and the way he was sent down the Nile, she knows that this must be a Hebrew child. She takes him in as her child and finds a Hebrew woman, his birth mother, to nurse him. The nurturing kindness that the Pharaoh’s daughter shows is in direct opposition to her father’s wickedness. Moses’ birth parents sent their three month old infant into the treacherous waters of the Nile and then they sent the older child, Miriam, to watch over him. What kind of parent sends their children into such a terrible place with threat of bull hippos and large crocodiles abounding? Moses’ birth mother exposed her children to these dangers in order to save their lives. A hard task for any mother to undertake. This part of the Parsha reminds me of the fear that many parents have about their queer children. Some would rather send their children out into the cold wet world than bear rejection by their communities because of having a queer child. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 575,000 to 1.6 million homeless and runaway youth are living on the streets from New York City to Los Angeles. Of these, between 20 and 40 percent are LGBT , according to the 2007 seminal study, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth: An Epidemic of Homelessness” by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF). Approximately 800 -1,600 queer homeless youth are estimated to live in San Francisco alone. A staggering 50 percent of queer teens experience a negative reaction from their parents when they come out and 26 percent are kicked out of their family homes by those same parents (1). The other children, like Miriam in the Moses story, are left as intermediaries between parent and queer sibling. These straight siblings pass along messages to parents about health and well being of their queer offspring but sometimes keep their relationship with such siblings a complete secret. These siblings act as the only connection to the young person’s roots. In fact, many queer youth will come out and disclose their sexuality to their siblings before anybody else in their families (2). The bond of siblings is one of familiarity beyond that of parent and child. However, some siblings will be like the parents and drop contact with their queer family. This causes queer youth to piece together a “chosen family” from friends and those in similar situations. These new forms of chosen family afford the support and encouragement that sustains these queer youth who have been cast aside by their birth families. Like Moses, queer youth are forced out of their homes and into the wide world. Where they either sink or swim depending on the current. They could find that they are eaten by the modern crocodiles of substance use or survival sex, or they just might find siblings and or chosen family that sustains and nourishes their soul; helping them thrive in a culture that does not value their humanity. Our own government devalues what it means to be queer, when they deny us equality on very basic rights like marriage and burial (3). These issues are not merely about our queer youth, they are societal and affect us all. When families and parents reject and neglect their children, when fear overrides the urge to nurture, then we as a people have to rise up and say “No More!” And in turning this Parashat around until it speaks to us as modern progressive Jews, we find the deeper meaning of G-d’s remembering his people during their bondage. G-d has not forsaken those who have been expelled from their childhood homes out of fear and ignorance, G-d remembers them and sends inspiration to sustain and nourish their chosen families. And in turn those families will become stronger and thrive in this harsh world. Like with Moses, G-d sends the Pharaoh’s daughter, in the form of chosen family, to take in both queer youth and adults alike and give them the love and understanding that they deserve. If in some form or another G-d eventually softens the hearts of those blinded by fear of difference, may we be ready to embrace our birth families when they are drawn to open those connections once again. Let’s not let the Pharaohs of the world win with their dastardly plot to take our children and throw them to the crocodiles, instead let’s nurture, inspire, sustain and nourish our communities and chosen families. Because if I have learned anything from Shemot, it is that every human being has a potential greatness that transcends all beginnings. References 1. http://www.thetaskforce.org/reports_and_research/homeless_youth 2. http://www.springerlink.com/content/a45044h7×4005r45/fulltext.pdf 3. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-segal/rhode-island-governor-vet_b_354888.html |

Author

Martin Rawlings-Fein (Delegate from AD 19) is a Jewish, Bi+, Trans, Father of Two, SF*EB BiCon Co-Founder, DEI Co-Chair, EdTech Specialist, Sometime Rabbinic Student, & Writer of Queer Liturgy. Archives

February 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed